- Blog

- Understanding 3 Different Types of Collusion on Food Delivery Platforms

Understanding 3 Different Types of Collusion on Food Delivery Platforms

Subscribe to Incognia’s content

Colluding might seem like a word reserved for high-stakes political maneuvers or other backdoor dealings, but it can happen anywhere—including our favorite delivery platforms. While you do your best to prevent fraud on your platform, collusion is a harder haystack needle to find than most, because it looks like a typical transaction from the outside.

All of the relationships mentioned in this post, including couriers and customers, couriers and app employees, and couriers and restaurants, are relationships that occur naturally in a platform’s day-to-day operations. This means that picking out the interactions that are actually collusion be more like finding a needle in a pile of needles than a needle in a haystack.

This certainly doesn’t mean that platforms are powerless against collusion, however. Today, we’ll take a closer look at the different forms collusion can take, and what delivery apps can do to protect themselves and their legitimate partners and customers.

Courier-customer collusion

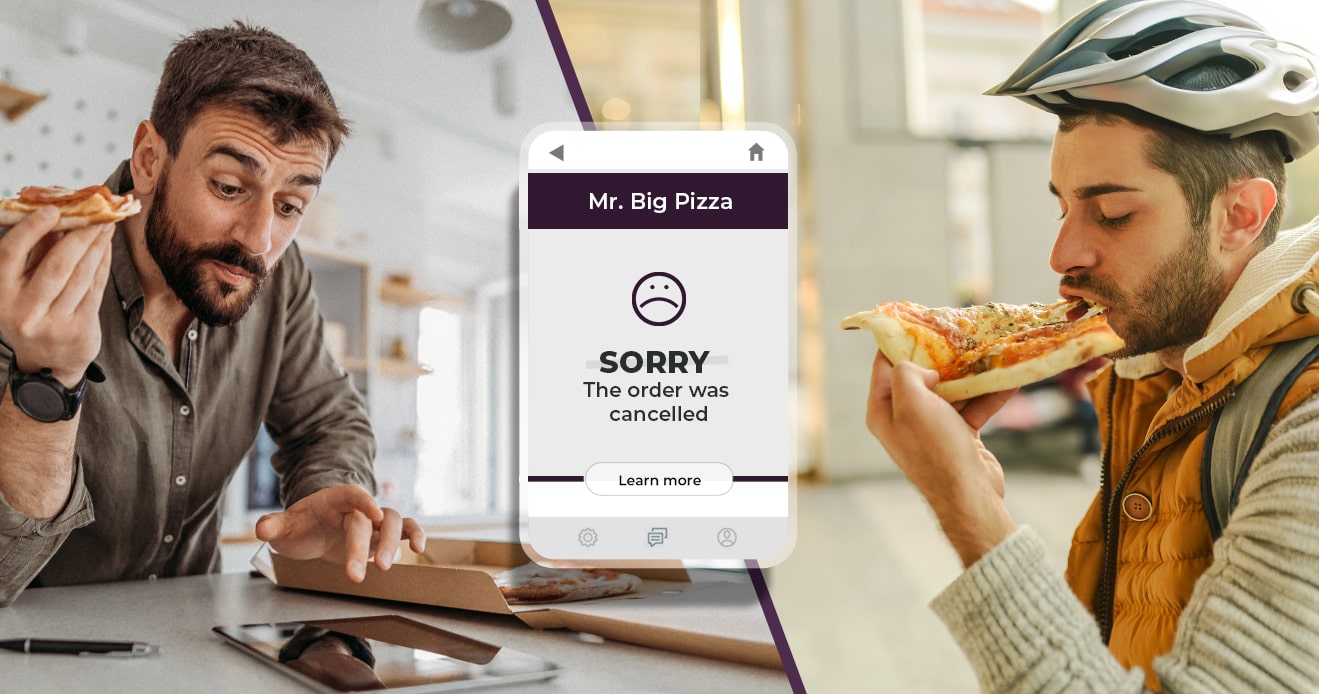

Likely the most common type of delivery app collusion, collusion between customers and couriers usually looks something like this: a customer orders food from the app, and after the driver picks up and pays for the food using their company-supplied payment method, the customer cancels their order through the app. The app takes the hit for the canceled order, and the driver and customer get to split the free food—depending on the app’s policies and the local fair pay laws for gig workers, the delivery driver might also get a partial payment for the trip they made to the restaurant before the cancellation.

While some abrupt order cancellations are par for the course for delivery apps, at scale and done with abusive intent, they stack up to a considerable chunk of change out of the app’s pockets. When you imagine even a small percentage of the leading apps’ millions-strong monthly active user bases playing into these types of schemes, the potential impact becomes clear.

Employee-courier collusion

With so much focus on drivers and diners in the fraud prevention space, it can be easy to forget sometimes that a platform’s own employees are also capable of fraud. While rarer, collusion between employees and couriers is certainly possible. Take this scenario for example: someone gets a job with a popular food delivery company, and encourages their friends or family members to sign up as couriers on that same platform. Using their newfound power as an employee, they grant their friends and family special privileges that other drivers wouldn’t have available.

The risks are a little higher with this type of fraud, as losing a full-time job is a bit different than losing access to a contractor account on an app where ban evasion might be possible, but it’s still important to keep an eye out for problematic privilege-granting between employees and drivers.

Restaurant-courier collusion

Restaurants are much more likely to be victims of fraud in the food delivery ecosystem than perpetrators, but it does still happen. One example of collusion between a courier and restaurant might look like restaurants ordering food to themselves under fake addresses, with the courier pretending to complete the order as though it were for a real customer. The restaurant can then artificially inflate its rating on the app, enticing other, real customers to order.

This type of collusion can also happen whenever the app grants incentives to the restaurant in the form of subsidizing discounts. For example, say the app wants a restaurant to offer a discount on smoothies, and they’re willing to pay the difference between the normal price and the discounted price to entice customers—essentially, a discount on the app’s dime to drive up sales. The restaurant might then create multiple user accounts to place fake orders for the discounted product, meaning the restaurant gets the difference money. A courier they’re colluding with would then “accept,” the deliveries to lend to their legitimacy, but nothing is actually prepared or delivered at any point.

Bonus: self collusion using multi-accounting

Different accounts don't always mean different users; sometimes, collusion occurs between any of the account types mentioned above, i.e., courier-side account and consumer-side account, but those accounts are actually owned by the same person.

In a famous case from Florida, two men were able to scam over $1 million from UberEats by creating accounts on both the courier and consumer sides of the app. They would place grocery orders through the consumer side, and then accept them on the courier side. Once the app provided them with prepaid credits for buying the groceries, they would cancel the order and use the prepaid credits to buy gift cards instead. Though this case of multi-accounting involved two people, it would’ve also been possible with one person making multiple accounts.

In cases where a grocery or food delivery app partially compensates drivers for canceled orders, a single person might place orders on the consumer side which they accept themselves on the courier side, before canceling and claiming the partial compensation. With multi-accounting, even a single individual can execute enough collusion between accounts to stack up to serious losses.

Thinking about solutions to collusion on delivery apps

Collusion can be a difficult beast to tackle because it imitates regular interactions between different parties, but there are some warning signs you can be on the lookout for, especially in the case of multi-accounting collusion.

Device ID is a powerful tool for recognizing repeat offenders, multi-accounters, and ban evaders. When paired with location, it becomes even stronger, because traditional device ID spoofing measures like factory resets won’t be enough to hide the phone’s true identity. With the ability to tie the same device or location to multiple difference user accounts, platforms can take action against multi-accounting and eliminate one tool fraudsters use to collude against the platform’s interests.

Fraud is constantly evolving, and fraudsters themselves are very opportunistic: where an opportunity for abuse opens up, they’ll eventually find and exploit it. That’s why it’s up to fraud prevention professionals and stakeholders to keep an ear to the ground and an eye on the latest developments on both sides of the fight.