- Blog

- The Fraud-as-a-Service Economy: How Fraudsters Make a Living Attacking Gig Economy Platforms

The Fraud-as-a-Service Economy: How Fraudsters Make a Living Attacking Gig Economy Platforms

Fraudsters have always existed, but the new era of mobile gig economy apps has allowed even small-time fraudsters to make a career out of defrauding platforms. Fraud-as-a-Service has become an underground economy fueling this abuse.

Subscribe to Incognia’s content

For those who prefer listening over reading, we've provided an audio transcription player below, allowing you to enjoy this post through your speakers or headphones.

Fraudsters are a little bit like freelancers who work for themselves. They invest time, money, and resources into their craft. They level up their tools-of-trade when they turn a profit. They look for ways to diversify their revenue streams and maximize their return-on-investment.

Like legitimate freelancers, fraudsters sometimes need skills or tools they don’t have—so like freelancers or any other business stakeholder, they look for a way to either develop those things in-house or to buy them from someone else.

This represents a business opportunity for more technically skilled fraudsters. They can develop the tools that other bad actors need, and sell them at a premium. That’s where Fraud-as-a-Service or “FaaS” comes into play.

And at the base of this fraud-as-a-service economy, fueling the demand, is a collection of gig platforms and user bases that fraudsters want to attack.

Key TakeAways

- Some fraudsters make tools for other fraudsters to make fraud easier, faster, and more cost efficient—these tools are called Fraud-as-a-Service or FaaS tools

- FaaS tools like emulators, app cloners, image injectors, and deepfake videos can help fraudsters bypass verification & scale fraud operations

- Tamper detection and advanced device intelligence are powerful tools for disrupting fraudster ROI and driving them away from a platform

Multi-accounting is the engine driving a lot of fraud schemes

Fraudsters are only willing to spend money on FaaS tools because they know they can turn a profit by committing fraud.

In the gig economy, multi-accounting is the engine that drives most profitable fraud types. Making as many fake accounts as possible on a food delivery or ride-hailing app isn’t usually profitable by itself, but those accounts are the raw resources that other types of fraud require to work.

A fraudster can take a large pool of accounts and abuse promos, abuse referral bonuses, commit collusion, commit ban evasion, and so on. Because of this, a lot of popular FaaS tools center around making it easier to create and manage a bunch of different accounts.

Incognia’s Global Head of Industry for food delivery and ride-hailing, Eduardo Pires, laid out the connection between multi-accounting and FaaS in a webinar with About Fraud:

“Fake accounts are basically the front door that Fraud-as-a-Service is willing to accomplish. Imagine if you have a food delivery app or a bank account or a fintech app. Any fraud needs an account to be performed…The professional fraudsters using this, they're going to commit a very high loss scam. And so when that happens, of course, the company, the food delivery app or the bank, is going to block the account and the account won't be able to make transactions anymore.

“Since they are professional fraudsters, they need more accounts to keep performing the fraud. And so, they need multiple accounts. The first thing that the Fraud as a Service is going to try to exploit is to create and manage a big pool of accounts.”

In the same webinar, iFood’s Head of Logistics, Raphael Vasconcellos, gives an example of what this kind of weaponized multi-accounting looks like in the real world.

At one point in time, some couriers with iFood were using tampered point-of-sale systems to trick customers into paying exorbitant amounts of money—where the PoS screen said $10, the actual charge might’ve been for $1,000, for instance.

Obviously, once the consumer realizes what’s happened, they report that courier to the app. The app responds accordingly by banning the courier, but that’s where multi-accounting comes in.

The courier goes right back to work on a fake account, allowing them to scam another victim, and another, and so on until they run out of accounts.

As Raphael says, “With Incognia, we discovered that we had multiple fraudulent accounts being accessed by the same mobile devices. [In one instance], the same device was accessing four different accounts and committing four different frauds of the same type.”

That fraudster was able to scam $2,668 from customers across the four different accounts. Tellingly, that same device had accessed an additional four accounts that hadn’t committed any fraud yet.

Eduardo Pires also provides a real-world example, this time with multiple accounts being used for voucher abuse instead of ban evasion.

In Eduardo’s example, a fraudster used DualSpacePro—an app cloning tool that allows multiple instances of an app to run on a single device simultaneously—to access 400 different accounts and consume almost €2,000 in vouchers in just 30 days.

“When it gets to this point, the company's completely blind already…at this point, by using an app cloner, what's going on is that the fraudster has found a way to bypass the device ID. And so the company doesn't have the proper data to fight fraud anymore.”

That’s how fraudsters monetize multi-accounting into money-making fraud schemes.

The next layer of this underground economy, the FaaS layer, is about how vendors make multi-accounting as easy as possible.

Fraud-as-a-Service tools make fraud a matter of optimized ROI

So, we’ve established that there’s money to be made in creating hundreds of fake accounts.

But how long does it take to create four hundred accounts on one app? And how do you access them all from one device without getting caught?

These are the two pain points that a lot of Fraud-as-a-Service tools address:

- Making multi-accounting easier, faster, and less tedious

- Making multiple accounts without getting caught

Let’s revisit the app cloner example from above. Depending on how much a fraudster is willing to pay for their app cloner, they could have as many as 20 instances of an app running at once on a single device.

That already makes it much easier to create and manage multiple accounts—running multiple instances means you can switch between accounts much more seamlessly than if you had to log out and back in each time.

A lot of app cloners also have features specifically for getting around device ID, meaning the fraudster’s one device will look like multiple devices to the platform.

But it’s possible to scale even further. Say you have an app cloner running 20 instances of an app at once. If you put that app cloner on a virtual device inside of an emulator program, you could also have multiple “devices” at once.

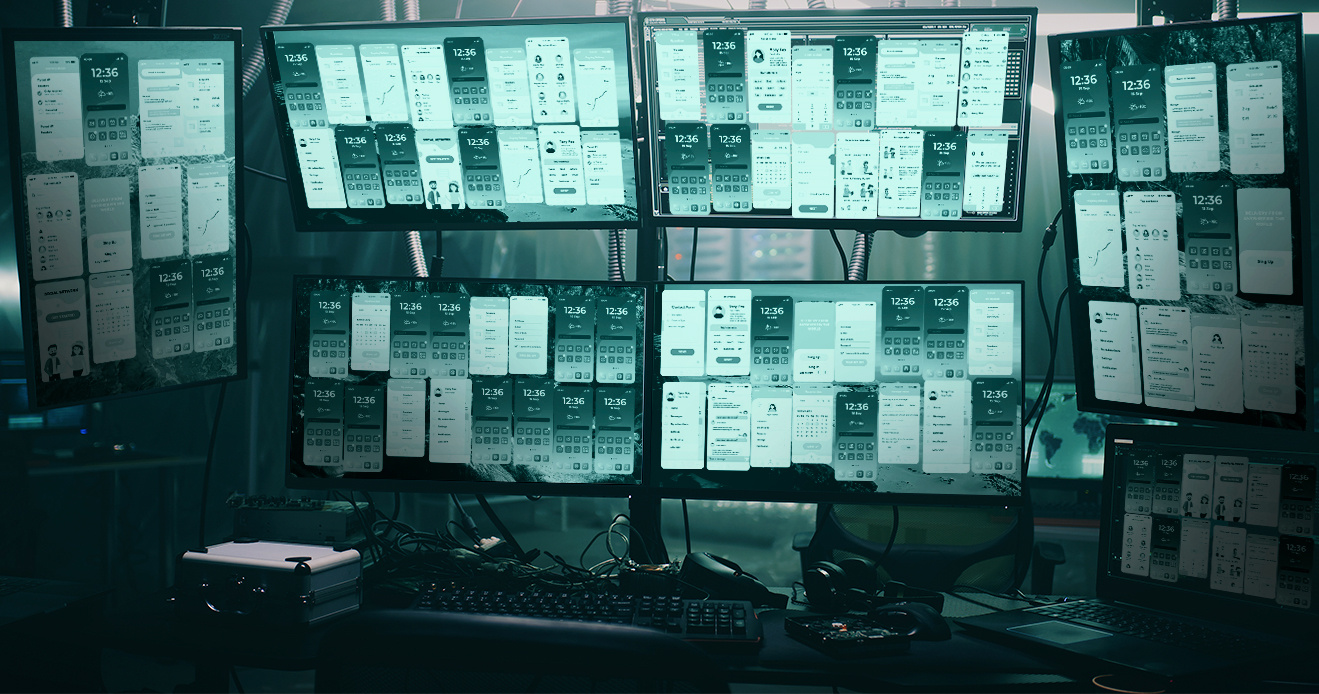

During the About Fraud webinar, Eduardo showed the slide below and explained,

“Here's an example of the emulators being combined with app cloners. We initially had one single device with multiple instances of Telegram. Now we have six devices, each of them with ten Telegram clones. So that's a very, very powerful and dangerous tool, because the fraudsters can commit attacks pretty much exponentially. So that's the kind of thing that we are seeing here at Incognia. And we are working hard every day to fight back against these kinds of tools. ”

Emulators and app cloners can help with both the tedium of multi-accounting and with defeating the device intelligence measures.

Some FaaS tools help with other roadblocks fraudsters might face during the onboarding process for a gig economy app, like completing user verification.

In this screenshot below, we can see a popular photoshopping service used by fraudsters to fake driver’s licenses and other documents.

Deepfake programs and image injection tools are even more examples of fraud-as-a-service tools that exist to defeat user verification.

The bottom line is that fraud-as-a-service tools mean that fraudsters can commit more fraud with less time, device resources, and money. It increases their return on investment.

Eduardo sums the FaaS benefit up,

“If we go back to the portable PoS scam, the earnings for the fraudsters were much, much higher than a donation to get the best app cloner available. Fraudsters calculate ROI all the time.

If they can purchase or subscribe to a tool that's going to generate 10, 20, 30x more in returns, why not? They're going to do it. And these tools can definitely help them leverage and make the fraud process much easier.”

Return on investment is the consideration at the core of the demand for fraud tools, and the demand for fraud tools means that more people are incentivized to find ways to attack and defraud gig apps.

But the way fraudsters consider their ROI is also a valuable insight for fraud fighters.

Fighting back and disrupting the fraud economy

For fraud fighters, making the return-on-investment for fraudsters as low as possible is a smart strategy for de-incentivizing fraud and abuse. After all, if they’re not making money (or a worthwhile amount of money), why bother?

One of the best ways to bring down fraudster ROI is to drive up the cost of one of their most critical resources: multi-accounting. If it’s too hard, expensive, or time-consuming for fraudsters to create multiple accounts on a platform, that’s a lot of fraud schemes that are already dead in the water.

With more resilient device intelligence, for example, it’s possible to re-identify devices after factory reset or app reinstallation. That means that a fraudster would theoretically have to buy a new device for every new account they want to make—for most fraudsters, that’s enough to encourage them to take their schemes elsewhere.

Tamper detection is another important tool in the fight against the FaaS economy. Tamper detection can be used to look for evidence of emulation, app tampering tools, app cloners, location spoofers, and other indications that a user might have bad intentions with a platform.

Fraudsters do what they do because they want the most profit for the least effort. But fraudsters aren’t the only ones with advanced tools at their disposal.

Using fraud prevention tools and technology like location-based device intelligence and tamper detection, we can cut fraudsters off from the profits of fraud.