- Blog

- Smart Friction: Targeting Your Friction Toward Fraudsters, Not Good Users

Smart Friction: Targeting Your Friction Toward Fraudsters, Not Good Users

Friction is often treated as a necessary evil, but what if it doesn’t have to be? In this post, we dive into the idea of “smart friction,” including insights from marketplace Trust & Safety stakeholders Holly Sandberg and Arūnas Umbrasas

Subscribe to Incognia’s content

For those who prefer listening over reading, we've provided an audio transcription player below, allowing you to enjoy this post through your speakers or headphones.

Friction is a hot topic in the fraud prevention world, and for good reason. Like fraud itself, there’s no one answer to the question of friction. How much, how little, where to implement it, and what the balance should be between friction and security are all questions with different answers depending on a business’s needs, resources, development stage, fraud challenges, user base, vulnerability, and more.

One thing is certain: at our current technology level, some friction is inevitable. It’s the job of user experience designers and fraud fighters to determine where that friction is and what exactly it looks like from the user side, and there’s no shortage of conversations being had about just that. But what’s less commonly talked about is how to target your friction—treating friction as a tool to be leveraged rather than an obstacle to be avoided and worked against.

Stakeholders shy away from friction because it pushes users away, but there are some users that you might actually want to push away: bad actors.

Incognia recently hosted a webinar called, “Scam Stopper: Seller/Buyer Verification on P2P Marketplaces,” where we invited Holly Sandberg, Director of Trust & Safety at Reverb, and Arūnas Umbrasas, Director of Data Science in Trust & Safety at Vinted, to talk with us about user verification and the challenges therein. One of the more insightful ideas to come out of this webinar was Holly’s callout of “smart friction.” That is, friction that works for you and your good users, and not against you.

Designing friction intentionally

We know that too much friction is bad. It frustrates users, leads to abandoned account creations, abandoned shopping carts, and, if it’s bad enough, an abandoned platform. No user enjoys having to enter a million multi-factor authentication codes or enter sensitive information like a credit card number just to open an account. With a platform’s growth in mind, it’s no wonder that we usually treat friction as something to be avoided whenever possible.

But this might not be the full picture: friction for bad actors is good, and in fact, it can be one of a fraud fighter’s best tools to de-incentivize fraudsters from trying to join their platform at all.

So, how do you walk the tightrope between friction that good users hate, and friction that bad users hate? How do you create friction that disproportionately affects bad actors, while leaving good users relatively unaffected?

The answer is to treat your friction as just another part of your fraud prevention strategy, and design it intentionally.

In the webinar, Holly mentioned that having conversations with user experience stakeholders is an important part of designing or implementing any new fraud prevention measures.

“[It’s important to be] smart before you ever get to the point where you're actually deploying friction about the way that you design it, having conversations, getting other stakeholders who aren't in the weeds involved early and often really partnering with them on it, not just sort of delivering something and saying, ‘Here's what we're going to do.’”

But what does it mean to design friction intentionally, rather than trying to write it out of existence as much as possible? The answer can come in the form of friction as a checkpoint—where you deploy those checkpoints and for whom can be an excellent strategy for targeting your friction.

Having different levels of intervention for different risks

Not every user has the same level of risk associated with their device and account, so it only follows that not every user needs the same level of verification or security measures in place before they’re allowed to interact with the rest of the platform.

Take this example: say that one user, User A, tries to create a new account with an aged email address, unfamiliar device, valid phone number, and no suspicious apps or other warning signs on her device. Then imagine that another user, User B, has a valid email and phone, but his device has some high-risk factors, like having an app cloner installed.

A strategy that employs smart friction might look like letting User A proceed without further checks needed, while asking User B to provide additional information or satisfy verification measures. This way, only the higher-risk signup attempt gets hit with the extra friction, and there’s still an opportunity to avoid a false positive if the user does turn out to be legitimate after all.

Like Holly explained it in the webinar:

“We're not trying to kill an ant with a sledgehammer, right? We are always looking and always thinking about user experience, always thinking about friction. So, not just the availability of specific features, but the customizability of available features and how we're able to apply those to our content in as smart a way as possible to minimize friction, to maximize efficacy of the steps that we're taking to protect the platform, and an understanding that that's likely to change frequently.”

Arūnas echoed the idea of risk scoring, saying:

“We have a version of a risk score going for users. From registration throughout their lifetime on the platform, but we also look at the aggregate of all users, and we have various methods that allow us to identify if something is going beyond the threshold that we would expect given the seasonality, given the marketing spend, given all these factors. Maybe the inflow is still too high. That means something is off and we can deploy deeper analytical investigations.”

The ant-with-a-sledgehammer analogy rings true: there’s no need to unleash the full force of multi-step verification and other high-friction fraud prevention measures against every user that tries to join the platform.

For fraudsters trying to maximize the volume of accounts they hold, friction costs them time, effort, and resources, meaning the more of it they face, the less likely they are to commit to that platform as one where they want to run their game. By leaning on your risk signals, you can target your friction towards your highest-risk accounts, managing a balance between how much friction good users experience and the security of the platform.

Passive signals and step-up verification

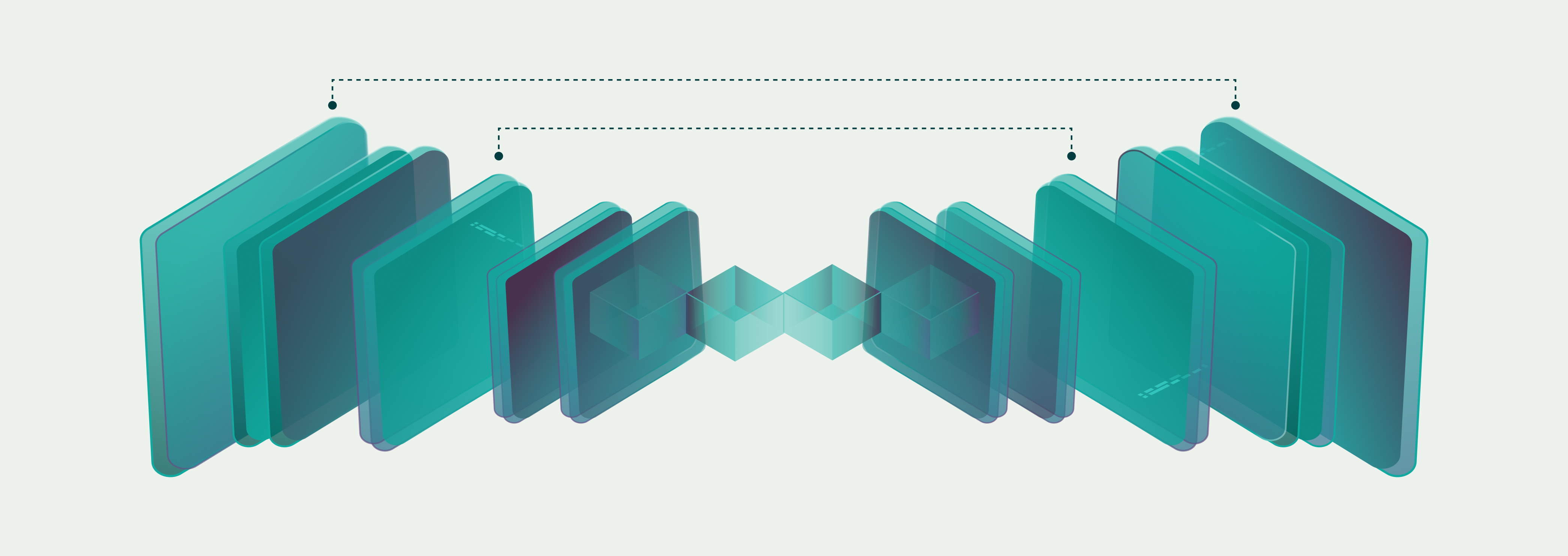

Friction can be even further minimized in how platforms go about assessing the risk of new and existing users. Passive signals represent the least friction because they can be collected without the user’s direct input, unlike requiring a photo ID and selfie or entering an email address and phone number.

As an example, Incognia uses location and device checks that happen in the background. We check for high-risk apps like app cloners and app tampering tools, whether we’ve seen the device before, whether the device’s location matches what the user reports about their locality, and whether the device’s location has been associated with fraud in the past. Our location technology, on average, identifies 82% of user risk instantly.

The user doesn’t have to do anything except grant location permissions for this to happen, but it gives fraud fighters a lot of actionable risk assessment information. Incognia uses location and device intelligence, but any reliable, passive signal like this can be a great tool for walking the tightrope between good UX and maintaining platform integrity. If the system returns a high-risk assessment, platforms can initiate step-up verification methods by asking only high-risk users to complete extra verification steps. That way, friction is contained and targeted, and the risk of false positives is managed by still allowing a conditional path forward for higher-risk signups.

As Incognia’s Director of Enterprise Accounts, Joe Midtlyng, put it in the webinar:

“An intelligent verification flow is something we're ultimately all after here—intelligent verification flow that can identify, in the most frictionless way possible, good users, and then identify those that are risky or questionable and step them up to other verification methods where you can introduce that friction that's necessary. From Incognia’s perspective, how we're helping clients is using a modern device and location signal early in that verification flow or waterfall as a low friction way to identify those good users with high accuracy and then allow platforms to step up to additional verification methods.”

Like the question of fraud itself, there’s no magic answer or silver bullet to the problem of friction and user verification. How much friction a flow contains and where will always be up to individual platform’s stakeholders to decide, but friction doesn’t have to be a necessary evil. When it’s incorporated into a fraud prevention strategy as just another tool that can be targeted toward fraudsters and away from good users, the risk of including friction into a verification flow can become an advantage in de-incentivizing bad actors to join a platform.